In Part 2 of our dive into vulnerability in design, we’ll look at how the lens of vulnerability can help designers to better understand people and their complex, individual thought processes, leading to better design for all.

In part one, I discussed how the landscape of financial services regulation has changed in recent years. I also looked at the approach of the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) in the UK, and how it potentially could provide a comprehensive framework for designers to consider what inclusive design looks like when applied holistically across a whole organisation’s activity.

Crucially, it offers a way of thinking about customers’ needs, and how, as human beings, any customer could be vulnerable at any time —whether due to health or life events, or differences in resilience or capability. And since vulnerability must not be a barrier for users to receive good outcomes, it has to be considered at the heart of the design of all products and services.

In part two, I’ll discuss how the lens of vulnerability can help us to consider customer journeys from new angles, and better understand customer experience for more people. It will show how small design decisions can have major, real-life impacts, and why it’s so important not to make assumptions about users or customers.

When thinking about experience design, one of the biggest challenges is developing a deep, true understanding of what something feels like for someone else, particularly someone we don’t know. The concept of vulnerability is really just another layer which can help us get to that point.

An example of different user thought processes

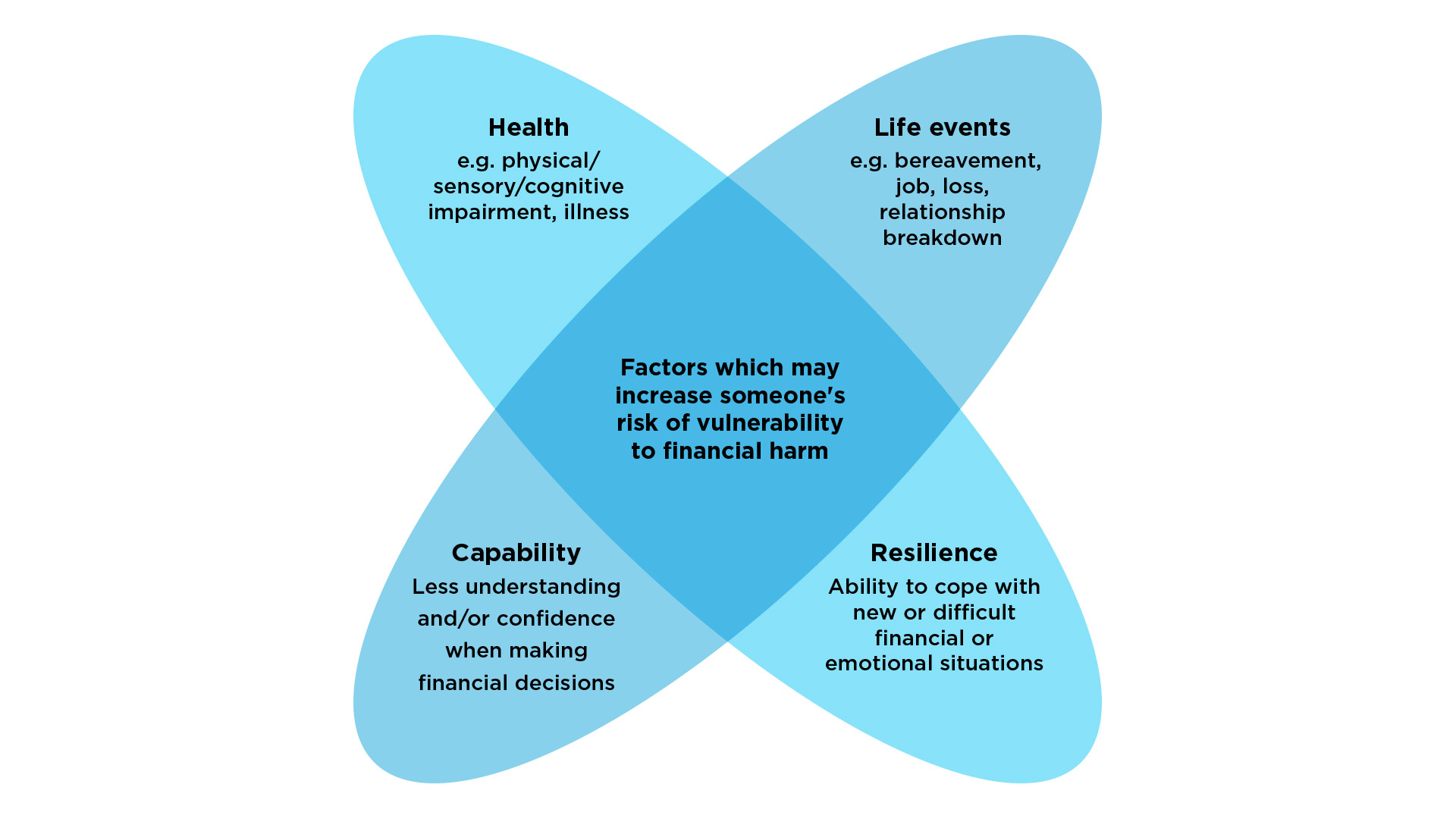

So what does “vulnerability” actually mean? We’ll use the FCA’s workings as a starting point. In part 1, we looked at the FCA’s four “drivers” of vulnerability and showed that they overlap; they can be situational and/or temporary, and most importantly that they can and do apply to almost everyone, at least at some point in our lives.

The four drivers of vulnerability outlined by the FCA are:

- Health, for example physical, sensory or cognitive impairments or illness

- Life events, for example bereavement, relationship breakdown or job loss

- Resilience, or the ability to cope with new or difficult financial or emotional situations

- Capability, or differences in understanding or confidence when making financial decisions

Looking at an example scenario, we can use these ideas to think about how it affects a customer’s experience.

Let’s take two customers of the same bank, Alex and Bobby. They don’t know each other, but they seem to have a lot in common: both in their early thirties, working in the same industry, with similar incomes and lifestyles. On the face of it—and based on the data the bank holds about them—they’re similar customers with similar needs, so they receive the same communications from the bank.

Alex and Bobby are both looking to buy their first car. Neither wants to spend more than necessary, but they both realise the purchase will still be significant.

Both need help to spread the cost over time. So when they each receive a letter from their bank offering a personal loan, both Alex and Bobby read with interest.

The letter Bobby received from his bank.

Alex is surprised at the amount that the letter suggests it is possible to borrow. Alex would love the latest electric car, but knows it’s not sensible to commit to repaying £50,000.

Instead, she finds a suitable car at £6,000. She decides to use £2,000 of savings and get a 0% purchase credit card with a limit of £6,000 from another bank. Because the card allows for interest-free repayments for almost two years, she can repay the money at an easily-manageable £180 per month. Alex is confident she’s made the right decision.

Bobby is also surprised that it’s possible to borrow so much, but his thought process is very different. Bobby has a tendency to make impulsive decisions, and knows he’s got to be careful around finances. But he doesn’t dismiss the idea entirely. He originally intended to spend around £6,000, but if the bank says he “could borrow up to £50,000”, maybe it is possible to get a better car?

Bobby deliberates for weeks. He looks at alternative financing options too, but there are so many variables, the decision becomes increasingly difficult and begins to occupy more and more of his headspace.

Eventually, he sees a car that catches his attention. It’s £15,000, much less than the £50k that he had mentally begun to account for— and more importantly, it ends his decision-making hell.

So Bobby takes out the loan. He has £2,000 in savings, so borrows £13,000 at 3.4% interest. This leaves him repaying around £235 per month for five years.

Bobby’s feelings are mixed. He loves his new car, but at the back of his mind, there is a nagging feeling that he may have regrets when he’s still paying the loan back in several years.

Vulnerability and accounting for differences between people

If we were designing solutions for a bank, we may well look at customers like Bobby and Alex from the outside and see similar profiles. We may well have synthesised them into the same persona group and imagine their customer journeys are likely to be extremely similar.

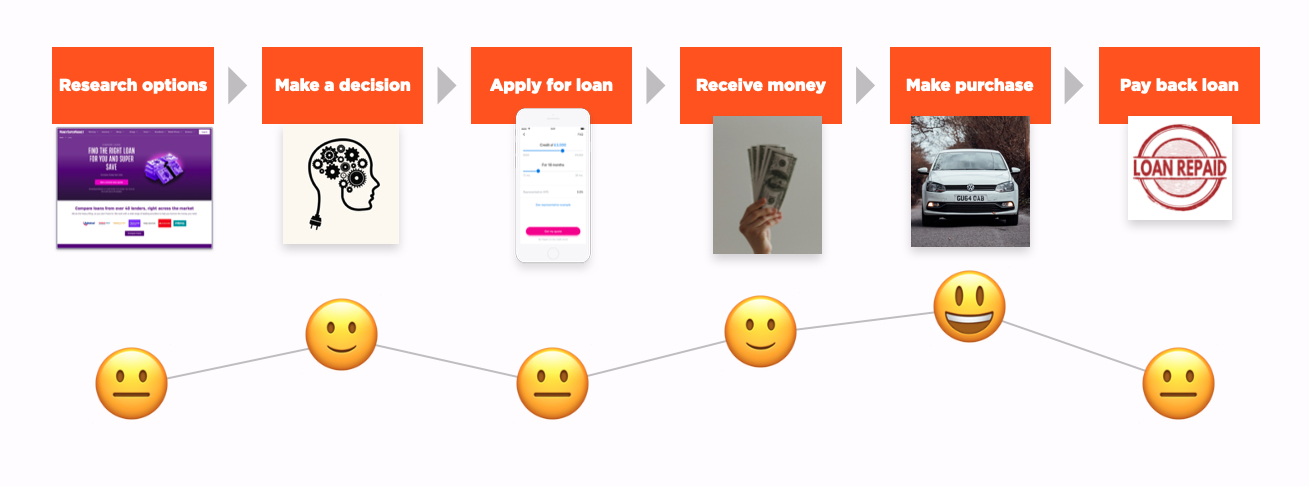

But in this scenario, each have had a very different experience. If we mapped journeys of their experiences, Alex’s may look something like this:

Alex's experience

She can come to a decision with relative ease, and is happy when she gets her new car. She’s not thrilled about the application processes, or the extra £180 expense every month, but it’s not exactly unexpected.

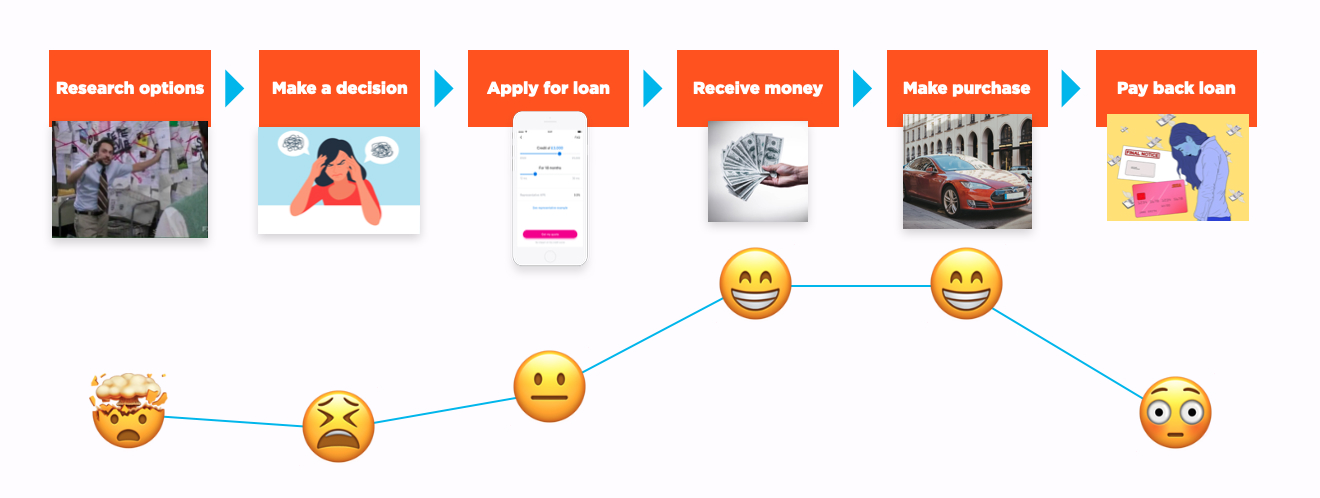

Bobby's experience map, however, might look something more like this:

Bobby's experience

Given that Bobby is of the same demographic, with the same career and income, it might be surprising that his experience is so different. He’s thrilled about having a car he never thought he could afford — but he found the decision-making unbearably stressful. It’s also dawning on him that five years is a long time to be making significant repayments. He’s now thinking it was irresponsible of his bank to suggest that he might borrow £50,000.

So why might these people with outwardly similar profiles have such different experiences?

One factor is: Bobby has ADHD. At work, he has routines to limit distraction, freeing up mental space to use his strengths of expansive thinking and creative problem-solving. But he’ll always face challenges, particularly with unfamiliar situations, where his difficulty filtering information means assessing consequences becomes overwhelming — often leading to decisions that seem impulsive.

It’s not just ADHD that could lead to a person’s experience map looking like Bobby’s. Struggling with numbers or language, an injury which limits mobility, or a temporary but stressful life event such as a busy period at work or relationship difficulties are just a few scenarios which might have an equally deleterious effect on one’s ability to make the decisions needed to finance a car purchase.

People are complex and rarely fit into boxes. There is only so much we can glean from their demographic information and the data we hold about them. We’re constantly navigating an unpredictable world, doing our best to adapt. We rarely make perfect decisions and frequently get things wrong.

Importantly, we all encounter challenging situations which make navigating the world even harder. As designers, it means that even though on a higher level we may be able to predict the success or failure of a design with some accuracy, our ability to understand how individual users or customers will respond is limited.

How can designers use vulnerability as a lens in practice?

Accounting for these kinds of difficult, but completely normal, human experiences is at the heart of our central idea: using vulnerability as an additional lens through which to view customer or user experience.

In the world of financial services, ideas of vulnerability are mostly centred around vulnerability to financial harm.

The four drivers of vulnerability help us understand that although we might be designing for a large customer or user base, they are not a monolith: they have complex individual circumstances which mean they will rarely act in perfectly rational ways.

The four drivers of vulnerability

In UX, there is an idea that if our designs work for edge cases, they’re likely to accommodate “usual” cases with room to spare. In reality, edge cases are usual cases — everyone’s circumstances are different, and we will all experience vulnerability at some point in our lives. Designers should always expect the unexpected.

But this doesn’t mean we have to design in the dark. In practice, it means looking at customer and user research and behaviour through an additional lens to gain a more holistic picture of people’s lives.

As well as understanding user needs and pain points, designers should also consider potential harm we could be causing through our designs, and mitigate it as far as possible. This is particularly important in sectors such as finance, where products can have significant consequences for their users. For example, introducing “positive” friction to slow the process down and allow the customer to consider all aspects of their decision. This may cause short-term frustration for a customer who wants to reach their goal quickly, but may prevent others from regretting a hasty decision.

We also need to understand the characteristics of the likely customers or users of a product or service. Customer characteristics may offer us vital information about their potential vulnerabilities, therefore helping us to mitigate potential harm. For example, if a bank prices its products aggressively, it may attract customers who are less financially resilient, and need more help to understand the product.

The same principles apply in other industries. We need to ask ourselves: what is the nature of the product we’re designing? What will it be used for and how will it be used? Who is using it? What are users’ personal circumstances like? How might they vary and how might the users be vulnerable?

Considering vulnerability benefits both businesses and users

In the scenario with Alex and Bobby, the communication the bank sent to the two customers didn’t improve its relationship with either. Alex used another bank to take out a credit card, and while Bobby did take out a loan, his trust was damaged because he feels he was encouraged to borrow more than necessary.

What could the bank have done differently to create a more positive engagement for both bank and customer?

Firstly, the bank could involve its customers more when designing to deepen their understanding of its customers’ lives and contexts. They could find out not only what they need, but also consider the wider potential impact on them if things were to go wrong.

It’s tempting to entice customers past point of sale by any means, but in the long run, it’s negative for both the bank and customer to sell loans that they will struggle to pay back. Instead, understanding people’s complex realities — our vulnerabilities as well as our goals — may well result in better-designed products and services that are more beneficial for customers and produce more sales in the long run.

Communication with customers may also benefit from this holistic understanding. Offering Alex and Bobby a more realistic loan may have built more trust for future valuable business, for example if they decide to take out a mortgage. Designing and speaking to customers’ actual circumstances is an opportunity to be more productive for all parties in the long run and encourage better quality, more sustainable and happier business.

Taking a design-led approach for success

It makes sense, then, that the FCA hint at a design-led approach in the Consumer Duty, as designers are well-placed to transform business for the benefit of both customers and businesses. In part one, I touched on the typical strengths of designers; we tend to be adept at understanding complexity and unpicking it to create innovative and useful solutions, we tend to have a holistic view and we’re used to considering peoples’ needs on an individual and a global level. Prioritising design can result in valuable and sustainable competitive advantage.

And as designers, it’s an opportunity to show we understand our responsibilities and the impact we can have. Often designers are in a unique position as a conduit between business and customer, giving us a holistic view of both. We can use this position to influence outcomes, balancing our empathy for individual users with the goals of the business, designing with responsibility and compassion.

As for vulnerability, understanding and discussing our own may be a good place to start this exploration. As humans, we’re all vulnerable to harm, we’ve all experienced it and we all need the support of others at times. In a complex and changing world, this may well be one of the few things we’ll always have in common.